Source: ERIC Clearinghouse on Disabilities and Gifted Education Reston VA.

There are many school factors that affect the success of culturally diverse students--the school's atmosphere and overall attitudes toward diversity, involvement of the community, and culturally responsive curriculum, to name a few. Of all of these factors, the personal and academic relationships between teachers and their students may be the most influential. This relationship has been referred to as the "core relationship" of learning--the roles of teachers and students, the subject matter and their interaction in the classroom.

Certain behaviors and instructional strategies enable teachers to build a stronger teaching/learning relationship with their culturally diverse students. Many of these behaviors and strategies exemplify standard practices of good teaching, and others are specific to working with students from diverse cultures. A number of these behaviors and strategies are listed below.

TEACHER BEHAVIORS

* Appreciate and accommodate the similarities and differences among the students' cultures.

Effective teachers of culturally diverse students acknowledge both individual and cultural differences enthusiastically and identify these differences in a positive manner. This positive identification creates a basis for the development of effective communication and instructional strategies. Social skills such as respect and cross-cultural understanding can be modeled, taught, prompted and reinforced by the teacher.

* Build relationships with your students.

Interviews with African-American high school students who presented behavior challenges for staff revealed that they wanted their teachers to discover what their lives were like outside of school and that they wanted an opportunity to partake in the school's reward systems. Developing an understanding of students' lives also enables the teacher to increase the relevance of lessons and make examples more meaningful.

* Focus on the ways students learn and observe students to identify their task orientations.

Once students' orientations are known, the teacher can structure tasks to take them into account. For example, before some students can begin a task, they need time to prepare or attend to details. In this case, the teacher can allow time for students to prepare, provide them with advance organizers, and announce how much time will be given for preparation and when the task will begin. This is a positive way to honor their need for preparation, rituals, or customs.

* Teach students to match their behaviors to the setting.

We all behave differently in different settings. For example, we behave more formally at official ceremonies. Teaching students the differences between their home, school and community settings can help them switch to appropriate behavior for each context. For example, a teacher may talk about the differences between conversations with friends in the community and conversations with adults at school and discuss how each behavior is valued and useful in that setting. While some students adjust their behavior automatically, others must be taught and provided ample opportunities to practice. Involving families and the community can help students learn to adjust their behavior in each of the settings in which they interact.

INSTRUCTIONAL STRATEGIES

* Use a variety of instructional strategies and learning activities.

Offering variety provides the students with opportunities to learn in ways that are responsive to their own communication styles, cognitive styles, and aptitudes. In addition, the variety helps them develop and strengthen other approaches to learning.

* Consider students' cultures and language skills when developing learning objectives and instructional activities.

* Facilitate comparable learning opportunities for students with differing characteristics. For example, consider opportunities for students who differ in appearance, race, sex, disability, ethnicity, religion, socioeconomic status, or ability.

* Incorporate objectives for affective and personal development.

Provide increased opportunities for high- and low- achievers to boost their self-esteem, develop positive self-attributes, and enhance their strengths and talents. Such opportunities can enhance students' motivation to learn and achieve.

* Communicate expectations.

Let the students know the "classroom rules" about talking, verbal participation in lessons, and moving about the room. Tell them how long a task will take to complete or how long it will take to learn a skill or strategy, and when appropriate, give them information on their ability to master a certain skill or complete a task. For example, it may be necessary to encourage students who expect to achieve mastery but are struggling to do so. They may need to know that they have the ability to achieve mastery, but must work through the difficulty.

* Provide rationales.

Explain the benefits of learning a concept, skill, or task. Ask students to tell you the rationale for learning and explain how the concept or skill applies to their lives at school, home, and work.

* Use advance- and post-organizers.

At the beginning of lessons, give the students an overview and tell them the purpose or goal of the activity. If applicable, tell them the order that the lesson will follow and relate it to previous lessons. At the end of the lesson, summarize its main points.

* Provide frequent reviews of the content learned.

For example, check with the students to see if they remember the difference between simple and compound sentences. Provide a brief review of the previous lesson before continuing on to a new and related lesson.

* Facilitate independence in thinking and action.

There are many ways to facilitate students' independence. For example, when students begin their work without specific instruction from the teacher, they are displaying independence. When students ask questions, the teacher can encourage independence by responding in a way that lets the student know how to find the answer for him- or herself. When teachers ask students to evaluate their own work or progress, they are facilitating independence, and asking students to perform for the class (e.g., by reciting or role-playing) also promotes independence.

* Promote student on-task behavior.

Keeping students on-task maintains a high level of intensity of instruction. By starting lessons promptly and minimizing transition time between lessons, teachers can help students stay on-task. Shifting smoothly (no halts) and efficiently (no wasted effort) from one lesson to another and being business like about housekeeping tasks such as handing out papers and setting up audiovisual equipment helps to maintain their attention. Keeping students actively involved in the lessons-for example, by asking questions that require students to recall information-also helps them to stay focused and increases the intensity of instruction.

* Monitor students' academic progress during lessons and independent work.

Check with students during seatwork to see if they need assistance before they have to ask for help. Ask if they have any questions about what they are doing and if they understand what they are doing. Also make the students aware of the various situations in which a skill or strategy can be used as well as adaptations that will broaden its applicability to additional situations.

* Provide frequent feedback.

Feedback at multiple levels is preferred. For example, acknowledging a correct response is a form of brief feedback, while prompting a student who has given an incorrect answer by providing clues or repeating or rephrasing the question is another level. The teacher may also give positive feedback by stating the appropriate aspects of a student's performance. Finally, the teacher may give positive corrective feedback by making students aware of specific aspects of their performance that need work, reviewing concepts and asking questions, making suggestions for improvement, and having the students correct their work.

* Require mastery.

Require students to master one task before going on to the next. When tasks are assigned, tell the students the criteria that define mastery and the different ways mastery can be obtained. When mastery is achieved on one aspect or portion of the task, give students corrective feedback to let them know what aspects they have mastered and what aspects still need more work. When the task is complete, let the students know that mastery was reached.

RESOURCES

Artiles, A. A. and Zamora-Duran, G. (1997). Reducing disproportionate representation of culturally diverse students in special and gifted education. Reston, VA: The Council for Exceptional Children.

Grossman, H. (1998). Ending discrimination in special education. Springfield. IL: Charles C. Thomas.

Kea, C. (1998, April). Focus on ethnic and minority concerns: Critical teaching behaviors and instructional strategies for working with culturally diverse students. CCBD Newsletter. Reston, VA: The Council for Exceptional Children.

Markowitz, J., Garcia, S. B., and Eichelberger, J. H. (1997, March). Addressing the disproportionate representation of students from ethnic and racial minority groups in special education: A resource document. Alexandria, VA: National Association of State Directors of Special Education. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED406810).

Based on Focus on Ethnic and Minority Concerns: Critical Teaching Behaviors and Instructional Strategies for Working with Culturally Diverse Students by Cathy Kea.

This blog is here for you. Its intention is to help and inform you as you navigate through your teacher education program.

Wednesday, July 29, 2009

Tuesday, June 30, 2009

Tuesday, June 9, 2009

Effective Teacher Commands

Here are some helpful hints from Jim Wright:

As classroom managers, teachers regularly use commands to direct students to start and stop activities. Instructors find commands to be a crucial tool for classroom management, serving as instructional signals that help students to conform to the teacher's expectations for appropriate behaviors.

Teachers frequently dilute the power of their classroom commands, however, by

-presenting commands as questions or polite requests. Commands have less impact when stated as questions or requests, because the student may believe that he or she has the option to decline. The teacher who attempts, for example, to quiet a talkative student by saying, "Tanya, could you mind keeping your voice down so that other students can study?" should not be surprised if the student replies, "No, thank you. I would prefer to talk!"

-stating commands in vague terms. A student may ignore a command such as "Get your work done!" because it does not state specifically what behaviors the teacher expects of the student.

-following up commands with excessive justifications or explanations. Because teachers want to be viewed as fair, they may offer long, drawn-out explanations for why they are requiring the class or an individual student to undertake or to stop a behavior. Unfortunately, students can quickly lose the thread the explanation and even forget the command that preceded it!

Using Effective Commands Teachers can reduce problems with student compliance and make their commands more forceful by following research-based guidelines (Walker & Walker, 1991):

Effective commands:

-are brief. Students can process only so much information. Students tend to comply best with brief commands because they are easy to understand and hard to misinterpret.

-are delivered one task or objective at a time. When a command contains multi-step directions, students can mishear, misinterpret, or forget key steps. A student who appears to be noncompliant may simply be confused about which step in a multi-step directive to do first!

-are given in a matter-of-fact, businesslike tone. Students may feel coerced when given a command in an authoritarian, sarcastic, or angry tone of voice. For that reason alone, they may resist the teacher's directive. Teachers will often see greater student compliance simply by giving commands in a neutral or positive manner.

-are stated as directives rather than questions. Perhaps to be polite, teachers may phrase commands as questions (e.g., "Could we all take out our math books now?"). A danger in using 'question-commands' is that the student may believe that he or she has the option to decline! Teachers should state commands as directives, saving questions for those situations in which the student exercises true choice.

-avoid long explanations or justifications. When teachers deliver commands and then tack lengthy explanations onto them, they diminish the force of the directive. If the instructor believes that students should know why they are being told to do something, the teacher should deliver a brief explanation prior to the command.

-give the student a reasonable amount of time to comply. Once the teacher has given a command, he or she should give the student a reasonable timespan (e.g., 5-15 seconds) to comply. During that waiting period, the instructor should resist the temptation to nag the student, elaborate on the request, or other wise distract the student.

As classroom managers, teachers regularly use commands to direct students to start and stop activities. Instructors find commands to be a crucial tool for classroom management, serving as instructional signals that help students to conform to the teacher's expectations for appropriate behaviors.

Teachers frequently dilute the power of their classroom commands, however, by

-presenting commands as questions or polite requests. Commands have less impact when stated as questions or requests, because the student may believe that he or she has the option to decline. The teacher who attempts, for example, to quiet a talkative student by saying, "Tanya, could you mind keeping your voice down so that other students can study?" should not be surprised if the student replies, "No, thank you. I would prefer to talk!"

-stating commands in vague terms. A student may ignore a command such as "Get your work done!" because it does not state specifically what behaviors the teacher expects of the student.

-following up commands with excessive justifications or explanations. Because teachers want to be viewed as fair, they may offer long, drawn-out explanations for why they are requiring the class or an individual student to undertake or to stop a behavior. Unfortunately, students can quickly lose the thread the explanation and even forget the command that preceded it!

Using Effective Commands Teachers can reduce problems with student compliance and make their commands more forceful by following research-based guidelines (Walker & Walker, 1991):

Effective commands:

-are brief. Students can process only so much information. Students tend to comply best with brief commands because they are easy to understand and hard to misinterpret.

-are delivered one task or objective at a time. When a command contains multi-step directions, students can mishear, misinterpret, or forget key steps. A student who appears to be noncompliant may simply be confused about which step in a multi-step directive to do first!

-are given in a matter-of-fact, businesslike tone. Students may feel coerced when given a command in an authoritarian, sarcastic, or angry tone of voice. For that reason alone, they may resist the teacher's directive. Teachers will often see greater student compliance simply by giving commands in a neutral or positive manner.

-are stated as directives rather than questions. Perhaps to be polite, teachers may phrase commands as questions (e.g., "Could we all take out our math books now?"). A danger in using 'question-commands' is that the student may believe that he or she has the option to decline! Teachers should state commands as directives, saving questions for those situations in which the student exercises true choice.

-avoid long explanations or justifications. When teachers deliver commands and then tack lengthy explanations onto them, they diminish the force of the directive. If the instructor believes that students should know why they are being told to do something, the teacher should deliver a brief explanation prior to the command.

-give the student a reasonable amount of time to comply. Once the teacher has given a command, he or she should give the student a reasonable timespan (e.g., 5-15 seconds) to comply. During that waiting period, the instructor should resist the temptation to nag the student, elaborate on the request, or other wise distract the student.

Wednesday, May 20, 2009

Five Classroom Management Strategies – They Really Work

Article by Kellie Hayden

Published on May 18, 2009

Strategy number 5 – Keep the lesson moving. If you have a forty-five minute period, plan three different activities. Try to get them up out of their seats at least once during the class period. Those students with pent up energy will thank you for it.

Strategy number 4 – Don’t lecture for the whole period. Students who are actively engaged in a learning activity are generally not disrupting the class. Hands-on activities work great for vivacious classrooms.

Strategy number 3 – Talk to your students. If you see them in the hall, in the cafeteria or at the grocery store, ask them how they are. If you see a student in the local newspaper, congratulate them. If they do something nice, tell them that you appreciate their kindness. This lets them know that you really do care about them.

Strategy numbers 2 -- When students are being disruptive by talking, poking, pulling or crumpling paper, go stand by them. This works best with boys. I have taught from the back of the room by the orneriest boys. This sends them a direct message to stop what they are doing. Most of the time they stop and get back to work.

Strategy number 1 – When you have stood by the student, talked to the student and kept them busy with lessons, and they still are disruptive, take them in the hallway. Ask them, “Are you OK?” It has been my experience that they crumble and tell you that they had a fight with their parents, didn’t get up on time or are having other issues. If they are defiant, send them on to the principal. In the last five years, I have sent very few kids to the principal’s office for classroom disruptions.

Kids are kids. If they are not actively engaged in the lesson, they will become actively engaged in something else – disruptive behavior. Try these five strategies to keep them learning.

Published on May 18, 2009

Strategy number 5 – Keep the lesson moving. If you have a forty-five minute period, plan three different activities. Try to get them up out of their seats at least once during the class period. Those students with pent up energy will thank you for it.

Strategy number 4 – Don’t lecture for the whole period. Students who are actively engaged in a learning activity are generally not disrupting the class. Hands-on activities work great for vivacious classrooms.

Strategy number 3 – Talk to your students. If you see them in the hall, in the cafeteria or at the grocery store, ask them how they are. If you see a student in the local newspaper, congratulate them. If they do something nice, tell them that you appreciate their kindness. This lets them know that you really do care about them.

Strategy numbers 2 -- When students are being disruptive by talking, poking, pulling or crumpling paper, go stand by them. This works best with boys. I have taught from the back of the room by the orneriest boys. This sends them a direct message to stop what they are doing. Most of the time they stop and get back to work.

Strategy number 1 – When you have stood by the student, talked to the student and kept them busy with lessons, and they still are disruptive, take them in the hallway. Ask them, “Are you OK?” It has been my experience that they crumble and tell you that they had a fight with their parents, didn’t get up on time or are having other issues. If they are defiant, send them on to the principal. In the last five years, I have sent very few kids to the principal’s office for classroom disruptions.

Kids are kids. If they are not actively engaged in the lesson, they will become actively engaged in something else – disruptive behavior. Try these five strategies to keep them learning.

Wednesday, May 13, 2009

Web 2.0 for the Classroom Teacher

Here is an excellent resource:

http://www.kn.att.com/wired/fil/pages/listweb20s.html

http://www.kn.att.com/wired/fil/pages/listweb20s.html

Monday, April 27, 2009

Special Education in the Science Classroom:

Here is a really good artical on teaching science.

http://www.glencoe.com/sec/teachingtoday/subject/special_ed.phtml

http://www.glencoe.com/sec/teachingtoday/subject/special_ed.phtml

Tuesday, April 21, 2009

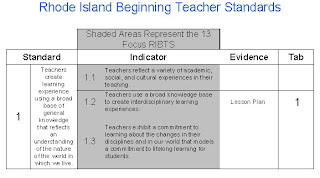

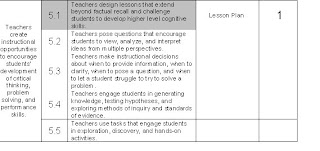

Setting Up Your Portfolio Matrix

1. Choose your first piece of work. ex. lesson plan

2. Put that piece of work behind Tab 1.

3. Look at the RIBTS that piece of work (lesson plan) addresses: RIBT 1.2 & 5.1

4. On your matrix beside RIBT 1.2 in the Evidence Box you write Lesson Plan, the name of the assignment, then the number of the Tab. Since it is the first piece, it will be behind Tab 1.

5. Since the lesson plan also addresses RIBT 5.1, beside that standard in the matrix you also write Lesson Plan and in the Tab box write number 1.

Every assignment has a tab.

2. Put that piece of work behind Tab 1.

3. Look at the RIBTS that piece of work (lesson plan) addresses: RIBT 1.2 & 5.1

4. On your matrix beside RIBT 1.2 in the Evidence Box you write Lesson Plan, the name of the assignment, then the number of the Tab. Since it is the first piece, it will be behind Tab 1.

5. Since the lesson plan also addresses RIBT 5.1, beside that standard in the matrix you also write Lesson Plan and in the Tab box write number 1.

Every assignment has a tab.

Tuesday, April 14, 2009

Creating Folders and Organizing Assignments and Artifacts in Tk20

By now you have many assignments and artifacts in Tk20 from fall 2008 through winter and now spring 2009. You can organize these assignments and artifacts into folders. It will make it easier for you to locate and organize and use the assignments you need now. Here is the procedure:

Creating folders

1. Click Courses on the Main Tabs.

2. Click on Assignments in the left side menu.

3. Then click on Edit Folders on left side menu.

4. On the next screen click on the add new button-a field will appear for you to write a name.

5. Create a name for your new folder-suggestion: Fall 2008.

Click the add new button again to create another folder-suggestion: Winter 2008-2009.

Organzing Assignments and Artifacts

6. Then click on coursework.

7. Next click in all the boxes that have fall assignments.

8. Then in the upper right hand side of the page click on the drop down menu that says Move to Folder and select Fall 2008 folder. All of the fall assignments will be moved to this folder.

9. Next click on the box before all the assignments for the winter.

10. Then in the upper right hand side of the page click on the drop down menu that says Move to Folder and select winter 2008-2009 folder. All of the winter assignments will be moved to this folder.

You can follow the same procedure to organize your artifacts.

Creating folders

1. Click Courses on the Main Tabs.

2. Click on Assignments in the left side menu.

3. Then click on Edit Folders on left side menu.

4. On the next screen click on the add new button-a field will appear for you to write a name.

5. Create a name for your new folder-suggestion: Fall 2008.

Click the add new button again to create another folder-suggestion: Winter 2008-2009.

Organzing Assignments and Artifacts

6. Then click on coursework.

7. Next click in all the boxes that have fall assignments.

8. Then in the upper right hand side of the page click on the drop down menu that says Move to Folder and select Fall 2008 folder. All of the fall assignments will be moved to this folder.

9. Next click on the box before all the assignments for the winter.

10. Then in the upper right hand side of the page click on the drop down menu that says Move to Folder and select winter 2008-2009 folder. All of the winter assignments will be moved to this folder.

You can follow the same procedure to organize your artifacts.

Monday, April 6, 2009

Wednesday, April 1, 2009

First Formal Review of Portfolio

Here is a check list that will be used for your first portfolio review. The matrix were emailed to you. You will need them. Print them and put them in your portfolio.

I wish we were using electronic portfolios, but we are not there yet. It might still happen before the end of your program.

_____ Sufficient progress towards meeting the thirteen pre-student teaching FOCUS RIBTS

_____ Standard indicator(s) are numbered and written

_____ CEC standards are numbered and written

_____ Diversity standards are numbered and written

_____ Description of evidence is in paragraph form and explained completely

_____ Narrative for each indicator/standard demonstrates an understanding of the connection between the competencies required within the standard and how the evidence submitted reflects the candidate’s understanding gained through experience and study.

_____ Original work with professor’s comments

_____ Format

_____ Appearance

_____ Name on spine of binder

_____ Typewritten

_____ Dividers

_____ No page protectors

_____ Matrix

_____ No spelling errors

_____ No punctuation errors

_____ No grammatical errors

I wish we were using electronic portfolios, but we are not there yet. It might still happen before the end of your program.

_____ Sufficient progress towards meeting the thirteen pre-student teaching FOCUS RIBTS

_____ Standard indicator(s) are numbered and written

_____ CEC standards are numbered and written

_____ Diversity standards are numbered and written

_____ Description of evidence is in paragraph form and explained completely

_____ Narrative for each indicator/standard demonstrates an understanding of the connection between the competencies required within the standard and how the evidence submitted reflects the candidate’s understanding gained through experience and study.

_____ Original work with professor’s comments

_____ Format

_____ Appearance

_____ Name on spine of binder

_____ Typewritten

_____ Dividers

_____ No page protectors

_____ Matrix

_____ No spelling errors

_____ No punctuation errors

_____ No grammatical errors

Thursday, March 26, 2009

Glossary of Math Teaching Strategies

Accelerated or individualized math: a system of having students work at different levels individually in one classroom. They progress by passing tests for each unit and move at their own pace.

Adjusted speech: teacher changes speech patterns to increase student comprehension. Includes facing the students, paraphrasing often, clearly indicating most important ideas,limiting asides, etc.

Curriculum Based Probe: having students solve 2-3 sheets of problems in a set amount of time assessing the same skill. Teacher counts the number of correctly written digits,finds the median correct digits per minute and then determines whether the student is at frustration, instructional, or mastery level.

Daily re-looping of previously learned material: A process of always bringing in previously learned material to build on each day so that students have a base knowledge to start with and so that learned structures are constantly reinforced.

Ecological approach/generate data from real life experiences to use in class: involves all aspects of a child’s life, including classroom, family, neighborhood, and community, in teaching the child useful life and educational skills.

Explicit timing: timing math seatwork in 30-minute trials that are used to help students become more automatic in math facts and more proficient in solving problems. Teacher compares correct problem per minute rate. Used to recycle materials and concepts.

Explicit vocabulary building through random recurrent assessments: Using brief assessments to help students build basic subject-specific vocabulary and also gauge student retention of subject-specific vocabulary. This list of teaching strategies and activities was developed out of a focused brainstorming process conducted with general education, special education and English as a Second Language teachers in Minnesota during the 2001-2002 school year. The list represents strategies and activities that teachers report that they use(or have used)to teach middle school-aged English language learners with disabilities. In most cases, the words that the teachers used to describe a strategy or activity are what is presented here in the glossary. A few of the strategies listed have definitions taken from professional literature. In the 2004-2005 school year NCEO will conduct single-case studies with ELLs who have disabilities that will be based on selected strategies from this list.

Graphic organizers: visual displays to organize information into things like trees,flowcharts, webs, etc. They help students to consolidate information into meaningfulwhole and they are used to improve comprehension of stories, organization of writing,and understanding of difficult concepts in word problems.

Model-lead-test strategy instruction (MLT): 3 stage process for teaching students toindependently use learning strategies: 1) teacher models correct use of strategy; 2)teacher leads students to practice correct use; 3) teacher tests’ students’ independent useof it. Once students attain a score of 80% correct on two consecutive tests, instruction onthe strategy stops.

Monitoring of progress through group and individual achievement awareness

charts: Using charts to build awareness and motivation of progress for students. The emphasis here is on progress so even students working at different levels can chartsignificant gains. Native language support: providing auditory or written content input to students in their native language.

Problem solving instruction: explicit instruction in the steps to solving a mathematical or science problem including understanding the question, identifying relevant and irrelevant information, choosing a plan to solve the problem, solving it, and checking answers.

Reciprocal peer tutoring (RPT) to improve math achievement: having students pair,choose a team goal to work toward, tutor each other on math problems, and then individually work a sheet of drill problems. Students get points for correct problems and work toward a goal. Reinforcing math skills through games: Using games to follow-up a lesson in order to reinforce learned skills and use the skills in another context.

Response journal: Students record in a journal what they learned that day or strategies they learned or questions they have. Students can share their ideas in the class, with partners, and with the teacher.

Student developed glossary: Students keep track of key content and concept words and define them in a log or series of worksheets that they keep with their text to refer to.

Students generate word problems: Have students create word problems for a specific math skill. Through the construction of a problem the students learn what to look for when solving word problems they are assigned. Tactile, concrete experiences in math: Using three dimensional objects in math instruction such as geometrical shapes, coins, or blocks used to form various geometrical shapes.

Think-alouds: using explicit explanations of the steps of problem solving through teacher modeling metacognitive thought. Ex: Reading a story aloud and stopping at points to think aloud about reading strategies/processes or, in math, demonstrating the thought process used in problem solving.

References:

Celce-Murcia, M. (Ed.). Teaching English as a second or foreign language. 3rd Ed.

Boston: Heinle & Heinle.

Chamot, A.U. & O’Malley, J.M. (1994). The CALLA handbook: Implementing the

cognitive academic language learning approach. New York: Addison-Wesley.

ERIC Digest. (1993). Teaching limited English proficient students to understand

and use mathematics. ERIC DIGEST 70. (EDO-UD-91-0). Document accessed on the web:

http://eric.web.tc.Columbia.edu/digests/dig70.html on February 23, 2001.

Laturnau, J. (2001, June). Standards-based instruction for English language

learners. PREL Briefing Paper (PB0102). Honolulu, HI: Pacific Resources for Education

and Learning.

Meyen, E.L., Vergason, G.A., & Whelan, R.J. (1996). Strategies for teaching

exceptional children in inclusive settings. Denver: Love Publishing Co.

Rathwon, N. (1999). Effective school interventions: strategies for enhancing

academic achievement and social competence. New York: The Guilford Press NYC.

Smith, T. et al. (1995). Teaching children with special needs in inclusive settings.

Allyn and Bacon.

Tuesday, March 17, 2009

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)